The Staggering Power of Workplace Atmosphere – And Why We Can Only Afford a Good Interaction Culture

The workplace atmosphere has such a staggering impact on well-being, resilience, engagement, and productivity that organisations can only afford a good one.

A culture with a positive code of conduct must be consciously built and actively led. Often, a poor atmosphere creeps in slowly due to continuous stress, and it has been overlooked for too long. Intelligent, civilised people are cordial and do their best until they can’t be bothered any more. The best leave first.

How we interact with one another and handle challenges shapes the workplace atmosphere and influences, e.g.

cognitive performance¹ ²

helpfulness¹

creativity¹ ³

productivity⁴ ⁵ ⁶

service quality⁷ ⁸

organizational commitment⁵ ⁶ ⁹

well-being and resilience⁵ ⁶ ⁹

team success⁵ ¹⁰

Who wants to try surviving today’s work life with only half a brain capacity?

At the core of negative stress is always a feeling of threat. Even a mild sense of rejection activates the same brain regions as physical pain¹¹.

Faced with a perceived threat, the brain reallocates resources from the boardroom to the border control, impairing logical thinking and self-management, and increasing misunderstandings and risk of conflicts.

In one experiment¹, being exposed to disrespect reduced the participants’ cognitive performance in word tasks and creative thinking by up to 60%, their math error detection by 43%, memory by 17%, and spontaneous helpfulness by 50%. Just witnessing a colleague being treated disrespectfully caused almost the same drop in performance.

What might numbers like these mean in your field with your workload?

In a large cross-industry, international interview study, 78% reported reduced commitment to their organisation after poor treatment. 48% said they put in less effort at work, and 38% admitted to intentionally working less well. One in four said they took out their frustration on customers. Only 12% actually changed jobs, meaning that the negativity often continues to circulate within the workplace. What is tolerated becomes normalised—and spreads.⁴

Naturally, each person’s EQ and current life stressors affect how long one can maintain well-being in a poor atmosphere. Still, any professional with normal resilience should not have to risk burning out because of work or need to leave to feel better elsewhere.

People make the culture and they can change it!

The first step is to name and sort the stressors as a team—into those you can influence and those you can’t. Then implement every possible improvement right away. Every sensible change in workflow increases a sense of control and of being heard.

To reduce stress, we must increase the sense of psychological safety.

You can start by assessing your team’s level of safety with this quick self-assessment (adapted from A. Edmondson, 1999). Everyone rates the following statements from 0 to 3 based on how well they apply to your team:

- Mutual respect and appreciation for each other’s work

- Trust that everyone is doing their best and not intentionally hindering others

- Helpfulness

- The courage to take risks in the team

- Support for those who make mistakes

- Ability to discuss difficult topics and ensure all voices are heard

- Diversity and differing views seen as a strength and resource

The benefits of psychological safety are well documented: better teamwork, increased job satisfaction, higher productivity and quality, greater creativity, adaptability, well-being, commitment—and happier customers.

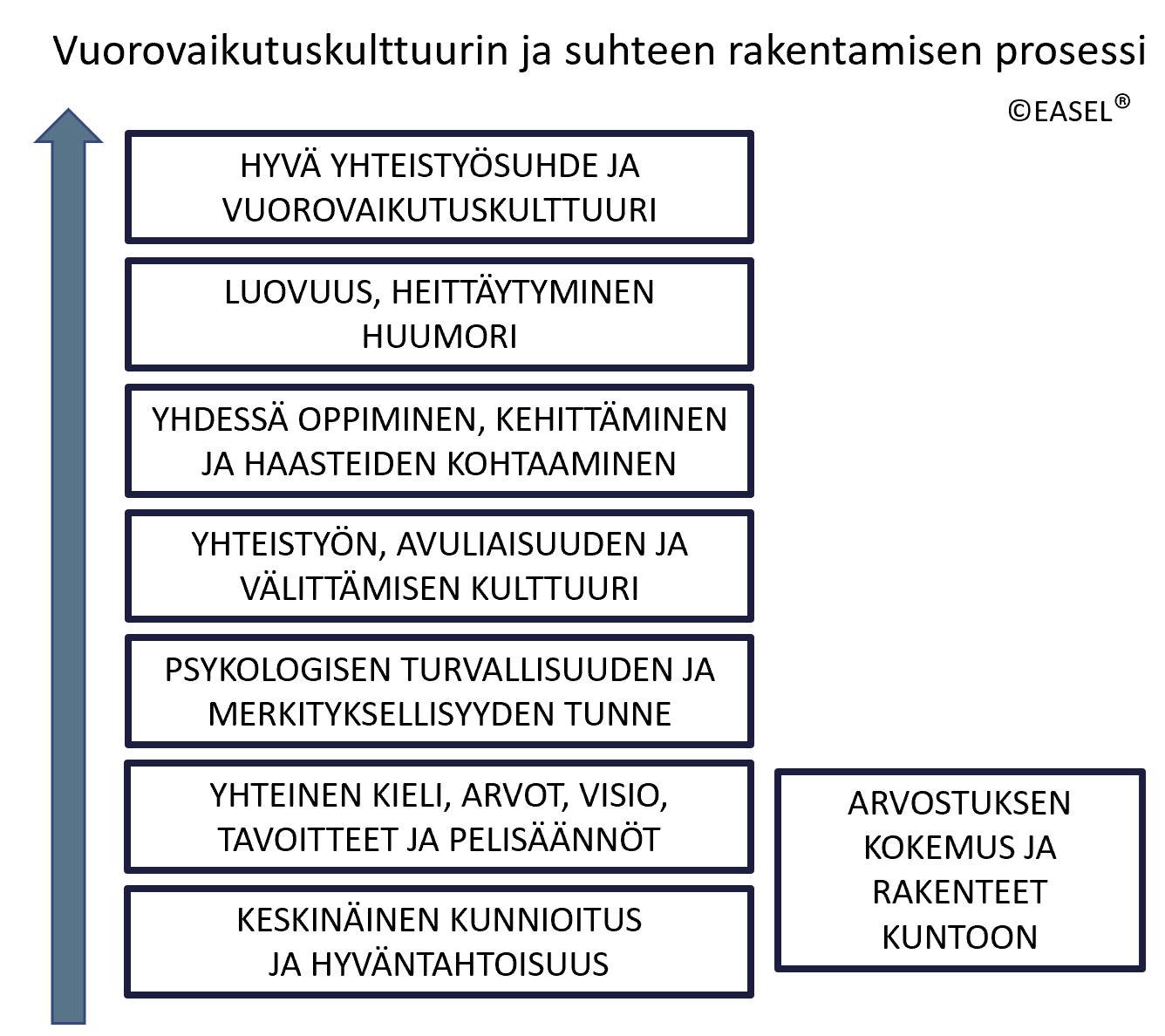

Relational Culture Must Be Consciously Built and Actively Fostered and Led

Good interaction—like any functional relationship—starts with mutual respect and goodwill. In every encounter, our brains assess within seconds: “Is this person’s intention good?”

In couple and family therapy, I often quote Harry Stack Sullivan: “Intimacy is when the other person’s needs are as important to me as my own.” There is no true intimacy without safety, and we only trust those who genuinely care about others’ well-being and are aware of how their actions affect others.

A great diagnostic question is: Do you not understand—or do you not care?

The deeper meaning of respect is beautifully captured in the Latin root of the word: respicere—“to look back.” Not deference or submission, but mutual recognition and a genuine attempt to understand the other’s message as they meant it. Disrespectful communication is essentially about elevating oneself and diminishing the other.

One young person once captured the idea of goodwill by saying, “If I try to make friends and mess it up, I still get another chance.” When the intention is genuinely kind, even corrective feedback is easier to receive.

The Power of Respectful Leadership

In a global survey of over 20,000 employees, no leadership behavior had a greater impact on employees than being treated with respect. Those who felt respected by their immediate supervisor reported:

- 56% better health

- 89% higher job satisfaction

- 55% greater commitment

- 92% better focus on core tasks

- 59% more likely to share information

- 71% more motivated to do their best⁴

In short: they were more likely to have access to their full cognitive capacity at work.

Next Steps in Building Culture

The second step is building shared language and understanding around the purpose of your work—what you’re trying to achieve, why it matters, and how. Every workplace should also define what kind of interaction culture it wants to uphold, and how psychological safety and trust will be practically supported.

In one study¹², simply using a kind conversational tone raised the sense of psychological safety by 35%.

The Fourth Step: Resilience

Oxytocin—the body’s “bonding hormone”—is released in safe, positive relationships and interactions. It strengthens collaboration, empathy, and helpfulness—and buffers against the effects of the stress hormone cortisol. In workplaces with high levels of trust (measured via oxytocin), people reported:

- 74% less stress

- 50% better productivity

- 76% higher commitment⁹

This fourth step builds comfort, engagement, well-being, and resilience—so that step five, involving learning, innovation, and navigating challenges, becomes possible.

A Note on Humor

On the upper rungs of this “ladder,” humor often comes up in training sessions—as a way to “break the ice.” Humor only works if it comes from genuine goodwill—and even then, it doesn’t always land.

One client described it like this:

“At my last job—about 50 people—the whole team gathered for my first day. The supervisor decided we’d play a ‘How well do we know each other?’ game. I went along, figuring I’d seem standoffish if I refused. But of course, the game turned funny for everyone else—because I didn’t know anyone and couldn’t answer a single question right. I never really found my place in that team.”

Good-natured humor, shared laughter, and inside jokes are signs of a thriving culture. But if you want to strengthen your workplace culture, don’t start with a party planning committee. Start from the first step.

Let us know how we can help.

—Mari